Operational Technology (OT) cybersecurity is a key component of protecting the uptime, security and safety of industrial environments and critical infrastructure. Organizations in the manufacturing, food and beverage, oil and gas, mining, chemical, petrochemical and other industries, as well as utility and power plant operators, focus on OT cybersecurity to safeguard operating technology assets, systems and processes from cyber attack and comply with strict regulatory requirements.

The connectedness of OT environments, IT-OT convergence and the proliferation of cyber-physical systems have expanded OT owners’ attack surface. Considering the importance of industrial process continuity, value of trade secrets and public safety-related impacts of a critical infrastructure (CI) compromise, it comes as no surprise that both organized crime and state-sponsored actors view industrial organizations and CI as lucrative targets for financial gain, espionage or cyberwarfare operations.

Correspondingly, cyber attacks on this sector have intensified. As Alert (AA20-205A): NSA and CISA Recommend Immediate Actions to Reduce Exposure Across Operational Technologies and Control Systems confirms, “cyber actors have demonstrated their continued willingness to conduct malicious cyber activity against CI by exploiting internet-accessible OT assets.”

Indeed, the breaches of water treatment facilities in the US and Israel, a major pipeline operator, a global meat processor, a multi-national brewer and others that captured the spotlight have been complemented by 585 incidents (270 with confirmed data disclosure) in manufacturing and 546 (355 with confirmed disclosure) in mining and utilities included in 2021 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR), as well as by many others. According to the 2021 Cost of a Data Breach Report by IBM and Ponemon Institute, the average cost of a breach was $4.65 million in energy and $4.24 million in the industrial sector, compared to the $4.24 million average for all industries.

Prevailing Threats

Threat actors’ initial activity against OT targets can be direct or indirect:

- Direct attacks inflict damage on a particular OT system. As KPMG explains, “Hackers may use remote connections to launch direct attacks, which was the case in the recent incidents at a power grid in Europe and a water plant in the US.” Once a system has been breached, attackers may insert malicious code into it to modify its control logic and cause a malfunction.

- Indirect attacks either breach IT systems to subsequently reach OT via lateral movement or target members of the OT supply chain, including service providers.

- In reference to attacks targeting OT that start with IT as the initial vector, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s “The Cyber Threat to Operational Technology” states that “ransomware operators have […] improved their ability to impact large corporate IT networks to the point that they can detect connected OT systems.” For example, ransomware targeting a “US natural gas compression facility traversed Internet-facing IT networks into the OT system responsible for monitoring pipeline operations, prompting a shutdown.”

- With respect to supply-chain attacks, threat actors often exploit the development process and inject malicious code into legitimate third-party software so that it carries a valid digital signature. Consequently, end users obtain the signed (but compromised) product through trusted download or update sites. A US supplier of network monitoring and management software and thousands of its government and commercial customers (including OT owners and CI operators) were impacted by such an attack. Further, threat actors hijack service providers’ privileged access to their clients’ systems. For example, ransomware operators recently compromised remote monitoring and management software used by Managed Service Providers (MSP) to install ransomware on many of their client networks at once.

As it pertains to specific attack techniques, Verizon DBIR cites that 98% of breaches in mining and utilities and 82% of those in manufacturing were caused by a combination of:

- Social engineering (#1 attack pattern in mining and utilities)

- System intrusions (#1 pattern in manufacturing), including those involving credential theft

- Web application attacks.

The report also identifies ransomware as a top action variety across manufacturing incidents, as well as a major threat to mining and utilities. Per BakerHostetler’s 2021 Data Security Incident Response Report, threat actors extorted from manufacturing companies ransomware payments averaging $1,403,876 (substantially more than the $910,335 average ransom in healthcare, for example).

Cybersecurity Strategies and Regulations

Numerous industry standards and frameworks help guide OT owners and critical infrastructure operators on their security-maturity journey. Some of the frameworks include the following:

- NIST SP 800-82 Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security offers recommendations on how to “secure ICS, including Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, Distributed Control Systems (DCS), and other control system configurations such as Programmable Logic Controllers (PLC), while addressing their unique performance, reliability, and safety requirements.”

- NIST IR 8183 Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) Manufacturing Profile provides CSF implementation guidance specifically developed to help reduce cyber risk in the manufacturing industry.

- American Water Works Association (AWWA) Water Sector Cybersecurity Risk Management Guidance includes guidelines to protect water sector Process Control Systems (PCS) from cyber attacks.

- Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) 08-09 provides guidance for nuclear power plant operators on how to create and implement a Cyber Security Plan required by Title 10, Part 73, Section 73.54, “Protection of Digital Computer and Communication Systems and Networks,” of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR 10 73.54) as part of the licensing process.

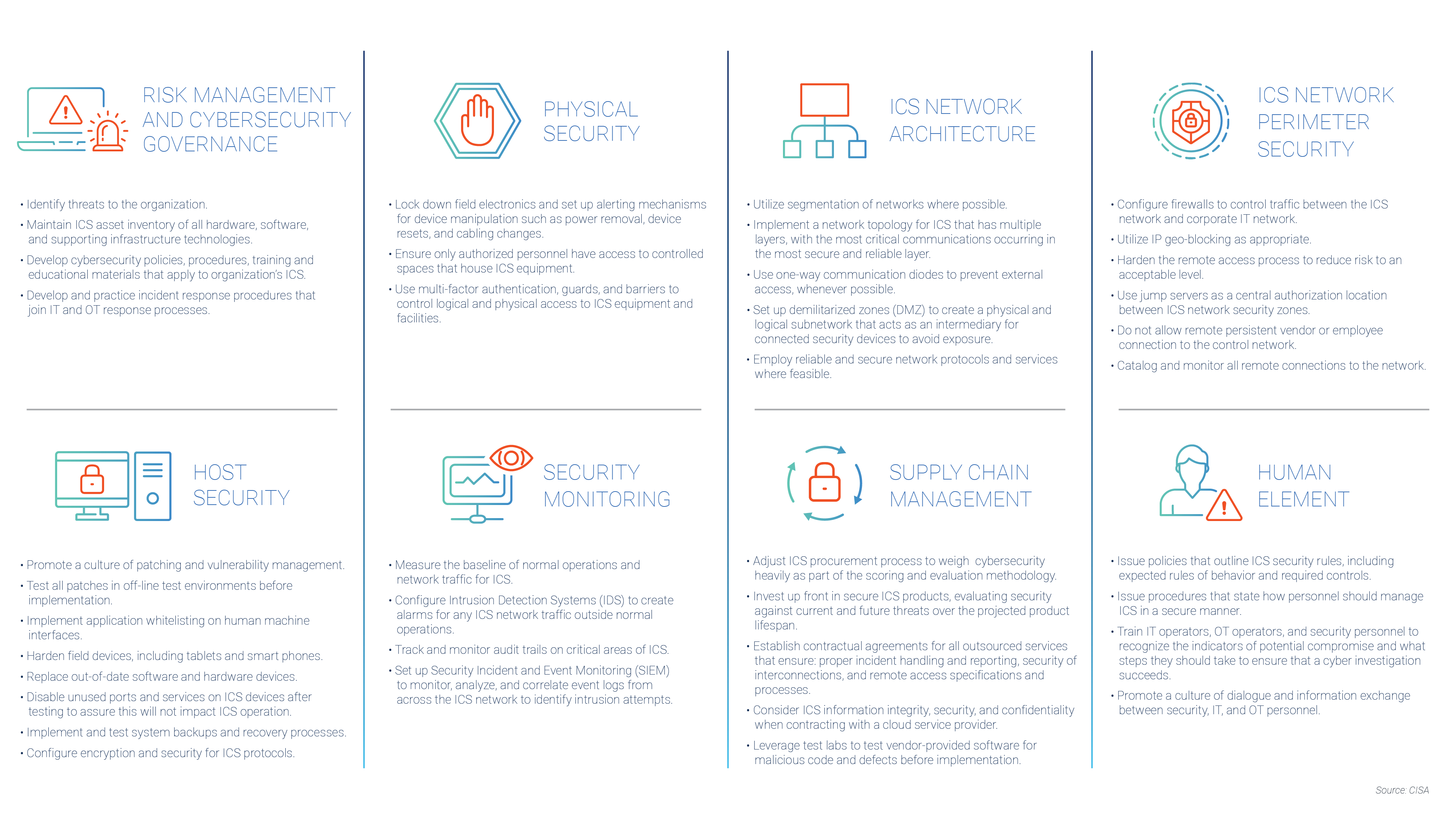

- CISA Recommended Cybersecurity Practices for Industrial Control Systems identifies the areas for OT owners to focus on when implementing a defense-in-depth strategy, as illustrated in the subsequent diagram:

Some of the key regulations and standards are presented below:

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) Critical Infrastructure Protection (CIP) standards outline mandatory requirements for operators of Bulk Electric Systems (BES) in North America. NERC CIP includes 11 standards subject to enforcement related to cybersecurity of the power grid — from security management controls to personnel and training to supply chain risk management.

- ISA/IEC 62443 standards provide a framework to address and mitigate security vulnerabilities in industrial automation and control systems (IACSs).

- CISA Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) program “identifies and regulates high-risk facilities to ensure security measures are in place to reduce the risk that certain dangerous chemicals are weaponized by terrorists.”

- CFATS applies to “facilities across many industries — chemical manufacturing, storage and distribution; energy and utilities; agriculture and food; explosives; mining; electronics; plastics; colleges and universities; laboratories; paint and coatings; healthcare and pharmaceuticals.”

- Facilities subject to CFATS must meet Risk-Based Performance Standards (RBPS) that include the following:

- Cyber-security requirements related to security policies, plans and procedures

- Access control

- Personnel security (e.g., user roles and accounts and third-party access)

- Awareness and training

- Monitoring and incident response

- Disaster recovery and business continuity

- System development and acquisition

- Configuration management

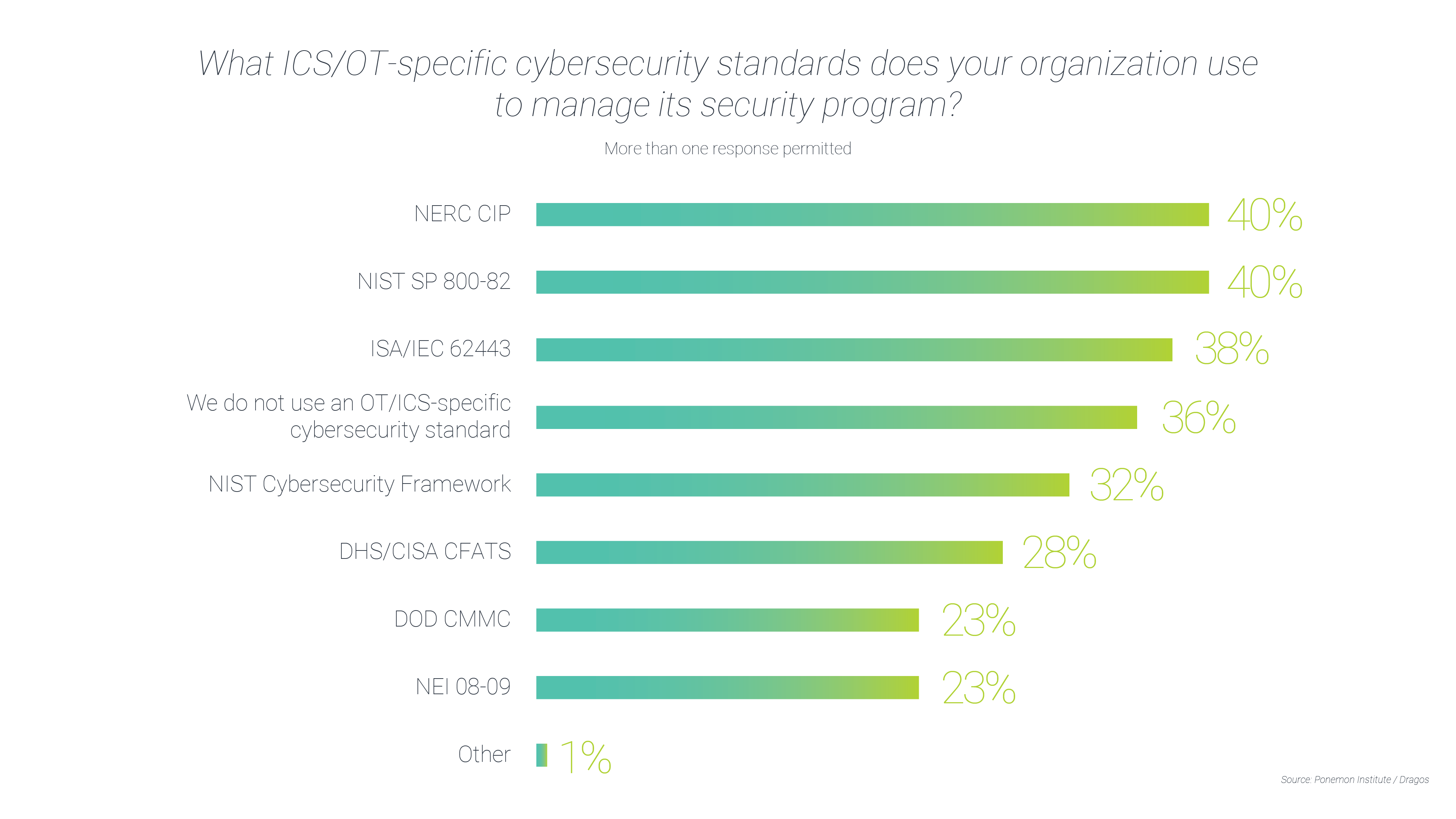

Which frameworks and standards do OT owners adhere to in real life? The “2021 State of Industrial Cybersecurity” survey of 603 IT and security experts in the US by Ponemon Institute/Dragos has uncovered that organizations abide by the following ICS-/OT-specific cybersecurity standards to manage their security program:

The Importance of Securing Identities and Access

Identity security controls are a critical foundation for any cybersecurity program, especially in the OT and IC spaces. NERC CIP standards, for example, include the following requirements pertaining to electronic access and identity:

CIP-004-6 — Cyber Security – Personnel & Training

Requirement R4 mandates that Responsible Entities (RE) have a documented access management program. Authorization for electronic access, including to designated storage locations for BES Cyber System Information, must be based on necessity. REs must periodically do the following:

- On a quarterly basis, verify that individuals who have access to BES Cyber Systems are, indeed, authorized to access them.

- Every 15 months, confirm that an individual’s privileges are the minimum necessary to perform their work function (the least privilege principle).

Requirement R5 directs REs to implement a documented access revocation program (to prevent acts of sabotage by disgruntled employees and remove access from transferred or reassigned staff when they no longer need it). REs must remove access in case of employee termination and eliminate unnecessary access in case of a reassignment or transfer within 24 hours. Non-shared accounts of terminated users must be revoked and passwords to shared accounts changed within 30 calendar days.

CIP-005-6 — Cyber Security – Electronic Security Perimeter(s)

Requirement R2 mandates that REs have a documented process for remote access management to “provide adequate safeguards through robust identification, authentication, and encryption techniques.” Specific requirements for Interactive Remote Access (IRA) include:

- Using an Intermediate System (proxy) to prevent direct IRA to critical assets

- Implementing encryption (terminating at an Intermediate System) and multi-factor authentication for all IRA sessions

- The ability to determine active vendor remote access sessions and disable them.

CIP-007-6 — Cyber Security – Systems Security Management

Requirement R5 mandates that REs have a documented process for system access control that includes:

- Enforcing authentication of interactive user access

- Limiting the number of unsuccessful authentication attempts or generating alerts when the threshold has been reached

- Identifying and inventorying all default or other generic account types (and removing, renaming or disabling them, if possible)

- Changing known default passwords and, for password-only authentication, ensuring minimum password length, complexity and password changes at least every 15 months

- Determining which individuals have authorized access to shared accounts.

CIP-013-1 – Cyber Security – Supply Chain Risk Management

Requirement R1 calls for a documented supply chain cybersecurity risk management plan for high and medium impact BES Cyber Systems. Mandated processes related to vendor remote access include:

- Revocation of remote access from vendor representatives after a notification by the vendor that access should no longer be granted

- Coordination of controls for vendor-initiated IRA and system-to-system remote access with vendors

- NEI 08-09 Appendix D: Technical Cyber Security Controls contains guidelines on Access (covering, among others, Account Management, Access Enforcement, Least Privilege and Remote Access) and Identification and Authorization of users and devices.

- CFATS RBPS 8 – Cyber includes under Security Measures both Access Control (e.g., Remote Access, Least Privilege and Password Management) and Personnel Security (e.g., Third-Party Cyber Support).

- AWWA Water Sector Cybersecurity Risk Management Guidance lists Access Control as one of the Recommended Cybersecurity Practices and Improvement Projects. Access Control measures include, among others, recommendations to secure PCS and enterprise system access, protect remote access and implement multi-factor authentication for all workstations.

- NIST IR 8183 CSF Manufacturing Profile covers Identity Management, Authentication and Access Control (PR.AC) under the Protect pillar and outlines these and other measures that are critical to preventing high-impact events that may have “a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on manufacturing operations, manufactured product, assets, brand image, finances, personnel, the general public, or the environment”:

- AC-1:

- “Deactivate system credentials after a specified time period of inactivity, unless this would result in a compromise to safe operation of the process.”

- “Monitor the manufacturing system for atypical use of system credentials.” Disable credentials associated with significant risk.

- AC-3 (remote access):

- “Allow remote access only through approved and managed access points.”

- “Monitor remote access to the manufacturing system and implement cryptographic mechanisms where determined necessary.”

- “Allow only authorized use of privileged functions from remote access. Establish agreements and verify security for connections with external systems.”

- AC-4:

- “Enforce account usage restrictions for specific time periods and locality. Monitor manufacturing system usage for atypical use.”

- “Disable accounts of users posing a significant risk.” Restrict and manage user access through non-local connections to the manufacturing system.

- AC-6:

- “Issue unique credentials bound to each verified user, device, and process interacting with the manufacturing systems.”

- “Ensure credentials are authenticated and the unique identifiers are captured when performing system interactions.”

- AC-7:

- “Implement multi-factor or certificate-based authentication for transactions within the manufacturing systems determined to be critical.”

- AC-1:

Implementing effective cybersecurity programs in OT and CI is vital to ensuring continued operations and public safety. With numerous frameworks and regulations in place, more and more OT owners and CI operators are advancing their cyber maturity. Identity security has always been and will remain an important milestone on this journey.

Learn More About Operational Technology (OT) cybersecurity

- Protecting the Grid: Addressing NERC CIP Requirements for Securing Privileged Access

- Preparing for the 5G Revolution Starts with Understanding Identity Security Threats

- Securing the Grid: Why Privileged Access Security is Key to Protecting Critical Energy and Utilities Infrastructure

- Securing Transportation Infrastructure

- Addressing the Security of Australia’s Critical Infrastructure with CyberArk Privileged Access Security

- PAM Customer Interview: Global Manufacturing

- Coca-Cola Europacific Steps Closer to Becoming the World’s Most Digitized Bottling Operation